The Pillage People

ES FIRÓ

When:Monday after the second Sunday of May, starting in the town square at 3pm.

Pirates arrive in the port at 5pm and seize the town at 8pm.

Christian victory by 9pm. Revelry follows

Where:Sóller and Port Sóller.

IMPORTANT: To gain access to the town square, you need to wear a special, free bracelet. We can arrange this

Every year the folk of Sóller rattle their sabres, sharpen their scimitars and ready their muskets for some rowdy fun. But the event they’re celebrating was no picnic: in 1561 the town was plundered and its inhabitants very nearly sold into slavery by maurading pirates from North Africa. It was a fate suffered by many other towns in the Balearics and the wider Mediterranean during the 16th century, when the Barbary corsairs and their sea lords, the fearsome Barbarossa brothers, ruled the waves.

Desperate times call for desperate measures and in 1570 King Felipe II of Spain and his advisors were considering measures that were desperate in the extreme–nothing less than the complete evacuation of the Balearic islands. The island of Formentera had already been abandoned. The populations of Ibiza and Palma were trembling behind their towns’ walls. Menorca’s capital, Ciutadella, had been reduced to ashes, the survivors shipped to bustling North African slave markets, and from Cuitadella and further afield, tales of massacres, desecrations of churches and violations of youth of both sexes sent shockwaves throughout the Christian world. Nowhere, it seemed, was safe from the Barbary pirates.

The people of Sóller, with time, would turn what had been the cause of so much terror and misery into an excuse for a lively, colourful fiesta.

Of course, there was nothing new about piracy in the Mediterranean. Since the Dark Ages it had been practiced by Christians and Muslims alike. For centuries French, Genoese, Maltese, Catalan and Mallorcan pirates had been ravaging each other’s and North Africa’s coasts. And raiders from North Africa gave as good as they got. But at the dawn of the 16th century, piracy took on a whole new dimension, as a state-sponsored holy war of attrition.

That this change took place was thanks largely to two cataclysmic events in the 15th century and two remarkable men, the Barbarossa brothers. In the east, Christian Constantinople, had fallen to the Ottoman Turks, who were now intent on spreading their empire. In the west, meanwhile, Muslim Granada had fallen to the Christians, creating waves of disaffected refugees bent on revenge. Most of them settled on the North African coast between Tangiers and Tunis, then made up of a string of small squabbling Muslim kingdoms and a chain of fortified Spanish posts, such as Oran, which the Spaniards had seized in 1509 after, in cold blood, massacring 4,000 of its inhabitants and sending the rest off to a life of slavery in Spain.

Onto this bloody stage swaggered the Barbarossa brothers, destined to build the ports of North Africa into bases for Barbary privateers and establish the practice of Barbary piracy, an institution that would terrorize Christian Europe for the next 300 years. The Barbarossa brothers, Aruj and Kheir-ed-din, came from a Greco-Turkish family that had converted to Islam. Their father had settled on the isle of Lesbos after its conquest by Sultan Mohammed II in 1462 and their mother, a Christian, was the widow of a priest. Nicknamed Barbarossa because of his red beard, the elder brother Aruj served in the Turkish navy before taking command of a pirate vessel. His voyages took him to the port of Tunis where he struck a deal with the king: in exchange for harbour facilities he was to pay the crown one-fifth of everything he captured.

Sóller maidens are captured by the pirates

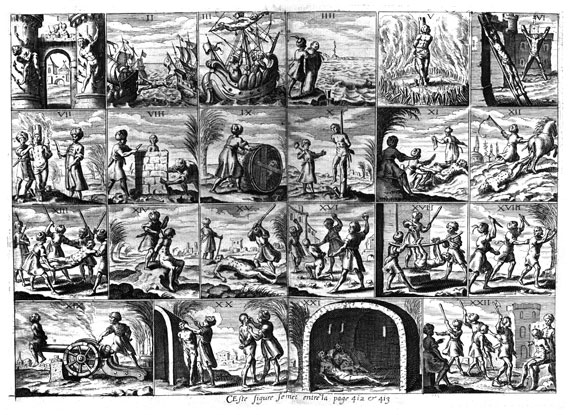

Turkish soldiers bring the heads of Christians to their commander. The scenes are from the cartoons for an astonishing series of tapestries now at Madrid’s Royal Palace which commemorate Emperor Carlos V’s war against Kheir-ed-din Barbarossa in 1535.

Portrait of Kheir-ed-din Barbarossa, half-length, holding a trident, Florentine school.

The naval superiority of the corsairs was provided by the greater speed and maneuverability of the Barbary galleys as compared to the Christian war vessels.

Turkish soldiers bring ship fodder for horses.

And he captured a lot. Hearing of his reputation, Algiers, then suffering a Spanish blockade, asked for his help. Aruj and his younger brother and their fleet rapidly took control of Algiers, put the Spaniards to flight, murdered the prince who had summoned them, and then turned on the local population. By 1517, Aruj controlled much of what is now Algeria, which he granted to the Turkish Sultan, who was only to happy to extend Ottoman dominion over North Africa.

Upon his elder brother’s death in flight from the Spanish in 1518, Kheir-ed-din, which means “defender of the faith,” took Aruj’s place as well as the name of Barbarossa. Appointed Governor-General of Algiers by the Turkish Sultan, the new Barbarossa surrounded himself with a splendid company of corsairs, the name given by the Mediterranean peoples to the Barbary privateers. Though called Moors, Turks and Saracens throughout Christendom, many of these corsairs were in fact former Christians, converted Italians and Greeks. Soon the new Barbarossa built a formidable fleet of galleys and turned his wrath on Christian Europe.

Though he was engaged for many years in subduing the native princes of North Africa, as a combatant at the forefront of the war with the Christians he soon became a great hero in the Islamic world. In 1519 he repelled a Spanish attack on Algiers and in 1529 he attacked Spain’s Mediterranean coast, helping thousands of moriscos, Spanish Muslims who’d been forcibly converted to Christianity, including 200 Mallorcan families, flee increasing intolerance in Spain. For the rest of the century, Barbary corsair attacks on Christian shipping and ports were relentless.

And the corsairs’ galleys didn’t stop at the Straits of Gibraltar; they raided as far north as Ireland and Iceland. In June 1631 Barbary pirates stormed ashore at the harbour village of Baltimore in Cork, capturing most of the villagers. And Icelanders still thrill to the saga of the maiden Tyrkja-Gudda, who, after being abducted and taken to the Algerian slave market, bought her own freedom and made her way back to her homeland through Tunisia, Italy and Denmark.

Some lucky captives never lost sight of their home shores, however: the pirates were often eager to broker a ransom deal with family members, friends and neighbours within hours of the attack, which was preferable to shipping them back to Algiers. Back in Algiers, unransomed captives were put on the auction block. Those unsold were taken to the bagnios, or slave prisons, where they remained at night, going out early each morning to toil on public works or as domestic servants or craftsmen. Many unfortunates worked as galley slaves–often a fate worse than death. In the slave prisons, missing nightly roll call was punished by 150-200 bastinadoes, or beatings on the soles of the feet.

While toiling all day, many slaves no doubt kept up their strength by entertaining ideas of escape. Some succeeded. William Oakley, for instance, built a boat from scrapwood and, with a gang of English slaves, reached Mallorca in five days, rowing furiously. Another way out, technically, was through conversion to Islam, but this was looked on with suspicion by some masters. Yet another route was to be ransomed by a religious order. The writer Cervantes was rescued after five years’ captivity by the Trinitarians, one of the many religious orders that made the ransoming of Christian slaves a part of their mission. Surprisingly, some slaves actually earned a small salary, and a few enterprising slaves even borrowed money from their masters and set up their own businesses. Eventually, some slaves earned enough money to buy back their own freedom.

The Barbary coast and the corsairs were beheld in horror and fear by Christian Europe. Scenes of torture from Histoire de Barbarie by Pierre Dan, published in Paris in 1637.

The watchtower above Port Sóller.

The watchtower in Banyalbufar.

By the 1540s the slave markets were working overtime. Thanks to the unholy alliance of Spain’s other great enemy, France, with Turkey in 1538, matters in the Mediterranean had worsened. Now the French king was allowing Barbary pirate fleets to winter in his ports. Sitting halfway between the pirates’ nest in Algiers and their winter base in the French port of Toulon, the Balearic islands were too tempting a target to miss.

Led by redoubtable sea lords such as Drub the Devil and Sinan, who was suspected of dabbling in the black arts, corsairs swept ashore to plunder Menorca, Ibiza, and the Mallorcan towns of Portocolom, Estellencs, Banyalbufar, Santanyí, Alcúdia, Valldemossa and Andratx. Ciutadella in Menorca was besieged by an invasion force of 140 ships and 15,000 fighting men. The outnumbered citizens bravely resisted but after nine days the city fell. Some 3,500 survivors of the ensuing massacre were carried away in chains. But the people of the Balearics were sometimes capable of defending themselves. An early-warning system composed of a chain of watchtowers was built along the coast and in 1550 the inhabitants of Pollença fought back, driving Dragut “the Drawn Sword of Islam” and his army back to their galleys, an event now commemorated every year in a week of festivals at the end of July.

The most celebrated–literally–victory over the corsairs, however, is that of Sóller on the morning of May 11, 1561. Under the leadership of Euldj Ali, an Italian renegade and later ruler of Algiers, 1,700 pirates sneaked ashore with the intention of raiding Sóller. Alerted, the menfolk of Sóller, aided by those of neighboring towns, rushed down to meet them in battle. However, the pirates had split into two groups and while the victorious Mallorcans beat 1,000 corsairs back to their boats, another band numbering 700 found Sóller unprotected.

The town was looted, and the women and children were seized–though not without some resistance. The valiant maidens or “Ses Valentes Dones”, the sisters Catalina and Francisca, defended their home and honour and managed to kill two Turks with sticks and stones.

As the pirates made their way back to the port with their plunder and captives, they met the Mallorcans returning from the coast in triumph. Now the Mallorcan men had to fight again, this time to free their captive wives, children and neighbours. Again the Mallorcans won the day and rescued their loved ones, in a battle raucously reenacted every year both in Port Sóller and in Sóller’s town square.

The Barbary pirates continued attacking Mallorca and the wider Mediterranean for centuries to come. Nations protected their fleets, somewhat, by paying protection money to the Barbary states. US ships came under attack in 1784 and, suddenly, many US sailors found themselves slaves in Algiers. It was not until 1815 that, after a series of naval victories, the US ended tribute payments. Some European nations continued coughing up until the 1830s, when France ended Barbary piracy with its conquest of Algeria.

But in 1570 even as King Felipe II of Spain and his advisors were pondering the evacuation of the Balearic islands, they were coming round to a more radical idea still–an alliance with rival powers Venice and the Papacy. The result was the Christian League, which just a year later dealt a crushing blow to Turkish naval supremacy at the famous battle of Lepanto, off the Greek coast.

Mallorca, though still to suffer future pirate attacks, could breathe a sigh of relief. New, stronger walls were built around Palma; and the people of Sóller, with time, would turn what had been the cause of so much terror and misery into an excuse for a lively, colourful fiesta.